In 2020, CLEA has been finding ways to strengthen networks between the initiators in community environment groups. Previous years have tested ways for committees of management (CoM) to work as peers to build the capacity of their groups. Finding a Landcare Network’s Question Without an Easy Answer, in the light of the Network’s likely future context, focused peer-to-peer (p2p) learning. This worked well while I facilitated, and when there was with a strong sponsor within the CoM, but attention to the Questions and to building capacity faded away when the sponsor left the CoM. Dacilitators do leave, and committee members change, often.

CLEA has also tested use of p2p learning in the State-level forums run by Victoria’s peak Landcare body. A little less chalk-and-talk and a bit more problem-solving between peers worked when I wasn’t there to shepherd through the use of p2p, but when I wasn’t the default reasserted itself: speakers and powerpoint presentations, with p2p at mealtimes.

Offered a fourth year of funding, I decided to have a crack at something that seemed simple enough – connecting the initiators in a community group to initiators in other groups. By initiators I mean the people who start things and keep them going. Most local Landcare groups have at most 3 or 4 initiators, Landcare Network Boards/CoMs will mostly be made up of initiators.

If the initiators could connect around their interests and find others like them, wouldn’t this speed up knowledge sharing, and support the enthusiasm people have for their shared interest?

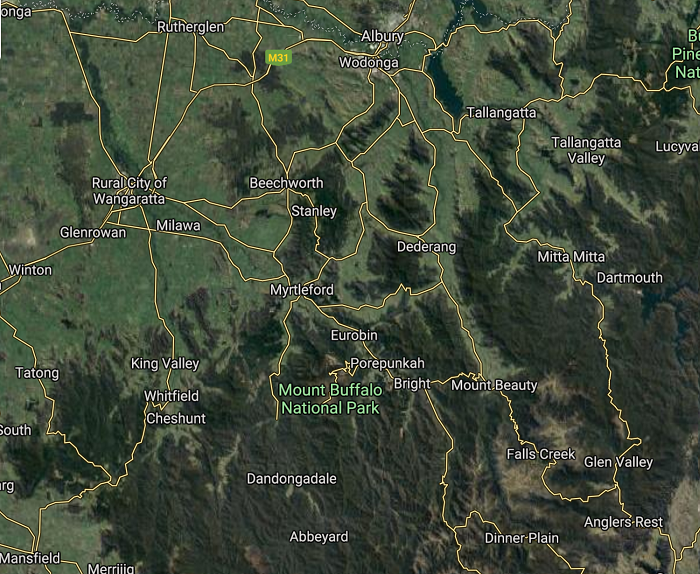

To get started, CLEA 2020’s trial site has been Victoria’s North East region, where the rivers that flow out of the Australian Alps run through valleys out onto plains and eventually to the Murray River.

What follows is a brief account of how that I unfolded.

Systemic co-inquiry

My starting focus: find what people in the region thought needed attention and with them, devise a way to address this. This is inquiry into a situation between people with differing perspectives. Year 4 of CLEA had the explicit question of how to support the development of peer-to-peer connection in networks, collective networks, the networks woven between individuals with a shared interest but located in different places in the region.

The specifics of what emerged in relation to strengthening networks you can find at the CLEA website,. Two conclusions: 1) there are four constraints that lock down community capacity and make community-based movements like Landcare look like another arm of government:

- Little institutional investment in building movement capacity

- Little interest by the movement itself in building its capacity

- Little practitioner investment in building networks

- Little community interest in diversity.

Conclusion 2: Prompt/support people to initiate the long conversations they want.

I wrote down more about what’s holding things back (see below), which is what everyone expects consultants do, but the other output was what I was most interested in as a practitioner, and that’s how to do 2. What I take to be a pretty good bet is to answer several questions:

What do you want to talk about, specifically, what do you want to take into a long conversation, and whom? Then what help do you need proposing that conversation?

I expect to have a crack at using these questions in the current Southern Rangelands Revitalisation Project, about which more if you get in touch ross.colliver(at)bigpond(dot)com.

Good day.

Four constraints on strengthening knowledge networks in the community environment sector

Little institutional investment in building movement capacity

In the Natural Resource Management (NRM) sector, government funders want projects that deliver countable on-ground outcomes, by which they mean biophysical outputs. While staff job descriptions in the NRM sector include building capacity, at group, Landcare Network, regional or State level, their actual time is pulled toward putting together the next project bid, starting the next funded project, or tidying up the last finished project. Capacity build is on the list, but other necessities sit higher up the list.

The capacity of the Landcare movement is effectively no-one’s job. Facilitators have only the rudiments of community development in their biophysically-focused degrees. Regional Landcare Coordinators attend to their CMA’s demands, not the development of Landcare Networks or groups. Regional Landcare Facilitators focus on agricultural production. The State Landcare team has few staff and no budget for development. The Minister’s Office invents policy without troubling itself about implementation.

There’s no sustained budget at State level for the professional development of facilitators, and no career path. Facilitators migrate in and out of positions, and in and out of the sector. The one third or so who stay in their positions for a decade or more develop an intimate knowledge of their communities and the institutional world in which Landcare is embedded, but there’s no systematic harvesting and sharing of their knowledge. Facilitators are solo operators.

The lack of attention to capacity goes hand in hand with the stead decline in Government spending on NRM. Policy has become a rebranding of funding criteria every few years around the next set of new fixes, packaged in a new program identity. The ‘National Landcare Program’ neatly appropriates the work of the Landcare movement, and gives Landcarers a taste of what some indigenous custodians of Country might have felt when the previous Federal NRM program badged itself as ‘Caring for Country’.

Targets become ever-more specific, and administrative arrangements ever tighter. Timelines for submission, approval and implementation continue to fit the work demands of funders, not of groups working on ground. Paid staff like local facilitators keep the system turning over; committees wait in hope of the next funding round and the spike of activity it will bring to their membership.

NRM is organised around bureaucratic ways of working. It uses contractual relationships organised around targets set by others, not community ways of working, which depend on voluntary collaboration around shared responsibilities. Because they think their future depends on it, Landcare staff and committees spend a lot of time looking up into the mechanisms of funding, and much less time looking out into the dynamics of their communities. The funding criteria never ask for the social analysis behind a project, just the polygon, and the project reporting never asks for what is shifting in the community, just the headcount of biophysical outputs. So the view of a landscape as essentially a biophysical phenomena is maintained.

What happened to the people in the landscape? What happened to the concept of a social-ecological system, where each stream of living activity influences the other?

Landcare groups and Networks have become the service delivery arm of decisions made elsewhere, a cheap option for stretched government budgets, but not a support for creative communities who know what needs doing and can mobilise the necessary knowledge and effort.

Little interest by the movement itself in building its capacity

Why aren’t more Landcare’s leaders approaching movement capacity as a thing in itself, something that can be grown, just like interest in soil health, or perennials in pasture systems, or biolinks? Reading case examples of network development in June Holley’s work in the USA, and following conversations between people developing networks internationally (for example, at SumApp, and Commons Transition, I’ve started to ask why the same conversations don’t seem to be breaking out here, in Victoria.

After the heady years of Landcare’s early growth, many groups have now spent two decades limping from funding round to funding round, holding onto their local base but not often expanding it. For dedicated Landcare farmers, the big changes have been made, the hard work done: it’s time to retire. Urban refugees arrive chasing sustainability and lifestyle, not production, providing a flow of customers for Landcare to pass on the basics of land management, and the churn rate as lifestylers return to cities leaves space for a new crop of novices looking to learn the basics of land management, and keeps Landcare busy providing adult education for lifestylers.

In the meantime, basic land management knowledge has been drawn into production systems. Corporate and next-generation family farmers are now reinventing agriculture towards more tightly managed production systems. Driven by the pressures of a warming climate, they lean toward new technology solutions, and the ethos and the on-ground gains of 30+ years of Landcare are on shaky ground.

Landcare continues to break into new territory in the way farmers think about their land—soil health the last decade, possibly regenerative agriculture in the next—but Landcare’s social knowledge remains local and tacit. Fundamental challenges, such as how to organise projects when people are no longer willing to join committees, or how to connect to young people, are pursued by each group and Network, but not collectively across groups.

Stalwart Landcare activists, in the Victorian Landcare Council and now in LVI, have held the State Government to its funding of local facilitators, but there’s been no room to think about capacity beyond that core funding.

When capacity is considered, by the movement and by government institutions, it is thought of as training that adds to people’s skills and knowledge from some store of established expertise, rather than as peer-to-peer interaction that mobilise the capacity of people committed to common goals. The movement can be forgiven for treading this path, because this is an assumption shared by most educational institutions, professional associations and by many large organisations, despite the evidence that most of the learning people use in practice is gathered on the job, in action, with their peers.

What has gone missing is the idea that Landcare is a movement of people connected across localities, who know they are strong when they think and work as a movement.

Little practitioner investment in networks

In CLEA 2020, I invited people into a process of co-inquiry. How could networks for collective good be strengthened? In relation to climate change, what were they pursing, and what conversations did they see needed more attention? When I documented each interview in a gritty single page, and sent it to them for comments and sign-off, a quarter of my respondents answered without prompting. I chased the others and pushed the response rate to 50%. When I asked for their thoughts on a first cut on the the themes across the 13 interviews, the response rate was about the same.

Why didn’t the people I interviewed called me back when I emailed the next round of documentation or tentative conclusions ? Why without my calling back would the inquiry have stalled?

Landcare staff and committees are chronically over-worked. Covid-19 has had a numbing effect on communication per se, and on initiative. But why did I feel, when I got on the phone to a facilitator, that I was talking weird stuff?

Community developers have network building in their professional lexicon; State and national level environmental organisations (like ACF and Environment Victoria) have been cultivating locally-based activist networks quite explicitly for a decade. Community environmental work is all about networks, so why is there little interest in the ways networks are developing around landscape and agricultural issues, and in how they could be better used?

Maybe the idea of people connecting to other people has been swamped by digital networking, and we have become befuddled trying to keep up with a proliferating set of platforms and by the outright abuse of personal data by enormously powerful digital companies. Landcare shares in the folk wisdom of the importance of networks, and in contemporary attunement to networking in a digital age. But the actual practice of ‘networking’ in Landcare has been narrowed to stuffing more email addresses into Mailchimp and keeping your Facebook and Instagram account up to date.

At practitioner level, NRM remains resolutely biophysical. Landcare committees staff their positions from the hard sciences, not the social sciences. They recruit from the field of social activism or community development, out of necessity: when the working language of funding criteria is the language of polygons, not community segments, of workshops conducted, not emergent narratives, you hire someone who can talk that language.

What’s lacking is a sensibility about the social that operates as an explicit practice of social influence.

Little community interest in diversity

Is there something in rural communities in Victoria that runs against the deliberate cultivation of networks? Taking the NE region as an instance, is there a culture that is suspicious of difference, of differing persons, a culture that values sticking with the dominant ‘us’, rather than valuing and happily embracing the various minorities of ‘them’.

In CLEA 2020, those I interviewed might have been convinced about climate change, but they were also apprehensive about public discussion of climate change, fearing a tongue-lashing from climate deniers if they speak out in public. They wanted to stay away from explicit attention to differences of view. Framed in this way, the slight mutual disdain between full-time producers and part-time farmers, and between urban residents and the farming community, starts to be a pattern. People draw away from differences, and retreat back into their familiar social identify, rather than being curious about the different other.

Landcare groups could engage these differences directly, but this is difficult territory. They don’t want to upset people, or be seen as divisive, so the differences sit there, out of public discussion. Perhaps the conservatism of rural communities is keeping Landcare away from the conscious use of networks to provide a platform for marginal points of view.

##########

Knowing the constraints is a starting point for finding and joining forces with the strengths that can break through the constraints. To read what CLEA is doing on this, check out recent posts at www.lviclea.org.o